Woke up to a winter wonderland at Charlotte Lake after our first night of sleeping in below freezing temperatures.

“I wonder if the snow loves the trees and fields, that it kisses them so gently? And then it covers them up snug, you know, with a white quilt; and perhaps it says, "Go to sleep, darlings, till the summer comes again.”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass

I recently returned from a beautiful five day trip in the Sierras where we experienced the full spectrum of weather; from lightning, thunder and snow to rain, ice and sunny blue skies, Mother Nature tried her hardest to give us a beautiful beat down. Our itinerary consisted of a 3-day trek to Charlotte Lake via Kearsage Pass from Onion Valley and back followed by a one-day trek up Mt. Langley via New Army Pass from Cottonwood Lakes Trailhead. We followed the weather closely so we were very prepared in terms of gear and trail safety but as always, we were thrown a few curve balls (lightning storms on the pass and on the verge of frostbite while packing away gear). At night, temperatures dipped into the low teens and we woke up most mornings to a beautiful winter wonderland. Both of my friends hiked their very first 14-er, I saw some fall foliage and experienced the first snow of the season, we picked up a crew of PCT thru hikers and drove them into Lone Pine, and picked up a solo JMT hiker and drove him to LAX from Lone Pine. I love chatting with thru-hikers and listening to their amazing experiences! This trip, although challenging, was a win for all of us.

As we approach the winter outdoor season, it is important to understand that Mother Nature can and will take your life. Yes, the snow is pretty and can be fun but it can also kill you. Each winter, there are at least 2,000 rescues in North America and at least 100 lives lost because experienced hikers are unprepared. Summer hiking is not winter hiking, there is a whole different skillset needed in the winter that has nothing to do with your summer hiking ability. The gear list also differs; depending on where you are going you will most likely need a helmet, an ice axe, crampons/microspikes and snowshoes and you will need to know how to use these. Each winter, I take a mountaineering course so I can practice my skillset and build on what I have already learned (same goes for skiing). I truly believe that if you do not practice this skillset on a regular basis in the winter then you should not be out in the elements attempting a summit.

Snow covered bear canisters. Icy bear canisters can be tough to open. I personally use the Bearikade canister and will use my quarter to scrape away snow and ice.

Shoulder seasons

Shoulder seasons are my favorite seasons to explore the outdoors in, but in my opinion, are the most dangerous seasons because the temperatures are low but not frigid, there is enough snow on the ground to get you into trouble and the weather can and will change on a dime. Hikers love getting on the trails as soon as they hear about the first snowfall, which can be a recipe for disaster. Strong winds and low visibility can make navigating difficult, ice-thaw conditions can lead to injuries, and low temperatures without the proper gear can lead to frostbite and hypothermia. True, you probably do not have to worry about avalanche signs and post holing during the shoulder seasons but there are still plenty of reasons why you need to be cautious and should brush up on your mountaineering skills. Shoulder seasons should be treated as middle of winter; regardless of what the weather forecast calls.

Flipping the bird to Kearsage pass. We got caught in a pretty bad storm a couple hundred feet from the top of this pass.

Big Pothole Lake just as the storm began to role in.

Winter Mountaineering Gear

Traction devices: Snowshoes vs. microspikes vs. crampons

Microspikes are best worn on fairly level hiking trails covered with packed snow or ice. They provide that little bit of extra traction that you need to when your boot treads stop giving you good grips. A car analogy is useful here: regular boots are like winter snow tires with a more aggressive tread, but when they start sliding, you put on tire chains to get more grip. However wearing microspikes means added weight on your feet, which can wear you out prematurely on a long hike. It’s often possible to defer putting them on with better footwork, especially on packed snow. For example, if you splay your feet out and walk like a duck uphill you can coax a little more traction out of your boots. While microspikes are marvelous winter traction aids, they do have their limits when you start to tackle higher angle slopes covered in ice. That’s when you want to switch to longer and sharper winter traction aid called a mountaineering crampon.

Mountaineering crampons are best worn on higher angle ice, ice-covered rock, or mixed ice and bare rock when you need a deeper bite and more solid footing to climb a slope. The chains and spikes on microspikes have too much “give” in them and are too short to penetrate deeply into ice when you need it to hold your full body weight. True mountaineering crampons attach to a very specific snow boot and do not fit a regular hiking boot.

Snowshoes have two functions: they provide flotation so you don’t sink as deeply into powdery or deep snow, which helps conserve your energy, and prevents post-holing which occurs when you sink into snow up to your thighs or waist (without them.) Snowshoes also have integrated crampons on their undersides that help provide traction on ice or packed snow and can be used instead of crampons in certain lower angle situations.

Crevasse rescue equipment

Climbing rope

Tent, sleeping mat, sleeping bag, water filter, pillow, sleeping bag liner and pack. For a list of my specific gear items, check out my gear list on a past blog post. One of my favorite winter gear items in my Sea to Summit Thermoreactor sleeping bag liner.

All of my gear from the previous picture fits into stuff sacks. Stuff sacks can help save space and keep your clothing dry in your pack. I use trail crampons by Hillsound for mild-moderate snow/ice conditions.

Food, stove, bear canister, cutlery and mug. Make sure you have enough calories to keep you warm on the trails.

Personal hygiene products. I use wipes, a trail bidet, a facial mask, sunscreen and chapstick on every single overnight trip.

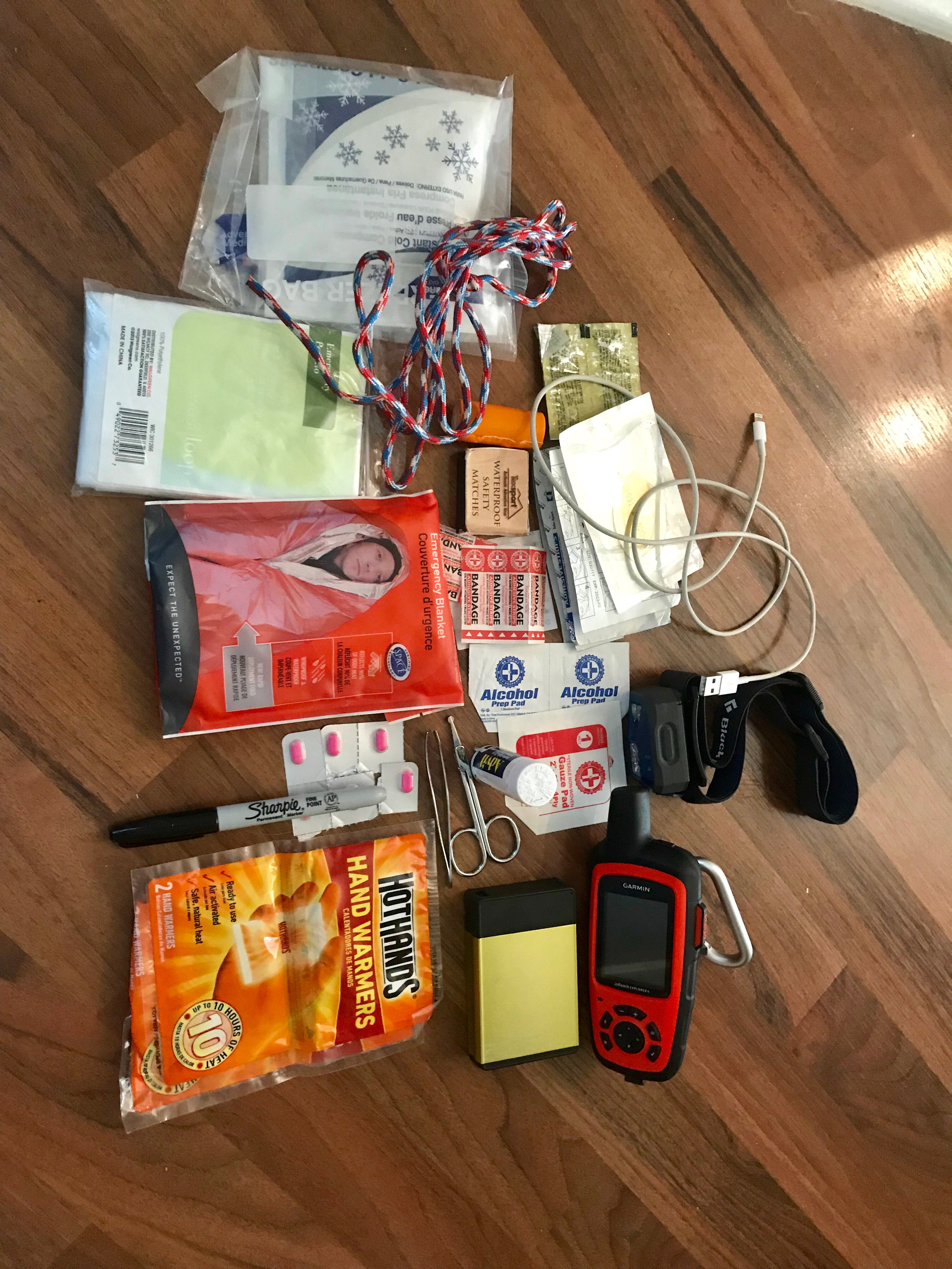

First aid kit and electronics. Ibuprofen, diphenhydramine (Benadryl), hand warmers, toe warmers, paracord rope, scissors, tweezers, safety pin, blister kit, marker (for outlining snake bites, rashes or wounds), matches, duct tape, poncho, emergency blanket, water purification tablets (in case my filters breaks or freezes), cold compress, Garmin InReach and Goal Zero battery pack. To see a full list and description of my emergency kit, check out my blog post on First Aid/Emergency Kits. I also have a blog post on Charging Electronics in the Outdoors.

Outdoor Mountaineering Classes

REI offers a bunch of mountaineering classes and adventure trips. They offer two levels of mountaineering skill classes up Mt. Baldy in the winter and also offer a great adventure trip with mountaineering lessons on Mt. Shasta. Check out their website for all the details. Depending on the location, these classes and adventures can range from $100- $800 but the price is well worth it.

Sierra Mountain Center offers lessons in mountaineering and backpacking out of Bishop. This is a great company and since the Eastern Sierras are ALWAYS guaranteed snow in the winter; this is a safer alternative than Mt. Baldy (in terms of cancellations due to lack of snow).

Shasta Mountain Guides offer a multitude of multi-day trips up Mt. Shasta for all levels of hikers. Many of these climbs also include mountain school where instructors teach mountaineering skills for individuals of all levels.

My definition of trail hot chocolate. Add a spoonful of peanut butter for extra protein and if you know me, you know I carry booze on the trail.

Read trip reports/ watch road conditions

If you are preparing a trip out into the backcountry where you will be adventuring into snow and ice, make sure to read the local mountain forecasts and compare multiple weather reports. My favorite sites are Mountain forecast and NOAA. You can search mountain ranges and tailor your elevation to see precipitation levels, temperatures, thunderstorm probabilities and wind speeds.

Are roads accessible? Most roads from the valley floor up to the trailhead are not plowed and therefore are not accessible after major storms. Always call the ranger station to check on road conditions and check with CalTrans to see if chains are required on major roads. Make sure you know how to use chains correctly. I personally do not enjoy putting on chains and therefore I do not travel on roads when chains are required.

View of Onion Valley from Flower Lake

Winter Rescue Statistics

A total of 46,609 people required search and rescue aid in the country’s national parks between 2004 and 2014.

The death toll from those incidents was 1,578, while another 13,957 people were injured or fell ill, data from the National Park Service show. Search and rescue costs topped $51.4 million during that span.

Nine people have died in the local SoCal Mountains in the last three years. Eight on trails and eight with light traction devices on their feet and poles in their hands.

Clothing

For a full guide on proper clothing and how to layer is freezing temperature, check out my blog post on Insulation. Photos of my gear for my recent cold weather backpacking trip are also below with details in the captions.

Morning views after it dumped snow and ice at Charlotte Lake.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is a decrease in the core body temperature to a level at which normal muscular and cerebral functions are impaired. Hypothermia can happen regardless of temperature for example, it can happen below freezing, at 40 degrees, at 60 degrees or any temperature below 98.6 degrees depending on the conditions and your peripheral circulation. Poor food intake, dehydration, cold temperatures, wet conditions, wind, improper clothing and equipment can all lead to hypothermia. When I am hiking in elevation and in cold temperature, I am ALWAYS eating calories regardless if I am hungry. If your body is calorie deficient, your core temperature will drop (same thing that happens during scuba diving). Alcohol intake can also lead to hypothermia because alcohol leads to vasodilation (dilation of your blood vessels), which creates blood flow away from your core.

Signs and symptoms of hypothermia

Watch for the "-Umbles" - stumbles, mumbles, fumbles, and grumbles, which show changes in motor coordination and levels of consciousness

Mild Hypothermia

Core temperature 98.6 - 96 degrees F

Involuntary shivering

Can't do complex motor functions (ice climbing or skiing) can still walk & talk

Vasoconstriction to periphery (fingers and toes changing white in color)

Moderate Hypothermia

Core temperature 95 - 93 degrees F

Dazed consciousness

Loss of fine motor coordination particularly in hands (can't zip up parka, due to restricted peripheral blood flow)

Slurred speech

Violent shivering

Irrational behavior (Paradoxical Undressing: person starts to take off clothing, unaware that he/she is cold)

"I don't care attitude" (flattened affect)

Severe Hypothermia

Core temperature 92 - 86 degrees and below (immediately life threatening)

Shivering occurs in waves, violent then pause, pauses get longer until shivering finally ceases because the heat output from burning glycogen (sugar) in the muscles is not sufficient to counteract the continually dropping core temperature, the body shuts down on shivering to conserve glucose

Person falls to the ground, can't walk, curls up into a fetal position to conserve heat

Muscle rigidity develops because peripheral blood flow is reduced and due to lactic acid and CO2 buildup in the muscles

Skin is pale

Pupils dilate

Pulse rate decreases

Old Army Pass (it was a tough haul going down).

Assessing Hypothermia

If shivering can be stopped voluntarily = mild hypothermia

Ask the person a question that requires higher reasoning in the brain (count backwards from 100 by 9's). If the person is hypothermic, they won't be able to do it. [Note: there are also other conditions such as altitude sickness that can also cause the same condition.]

If shivering cannot be stopped voluntarily = moderate - severe hypothermia

If you can't get a radial pulse at the wrist it indicates a core temp below 90 - 86 degrees

The person may be curled up in a fetal position. Try to open their arm up from the fetal position; if it curls back up, the person is alive.

Sunrise over New Army Pass on Langley.

Treating hypothermia in the backcountry

1) Reduce Heat Loss

Additional layers of clothing

Dry clothing

Increased physical activity

Shelter

2) Add Fuel & Fluids

It is essential to keep a hypothermic person adequately hydrated and fueled.

Food types

Carbohydrates - 5 calories/gram - quickly released into blood stream for sudden brief heat surge. These are the best to use for quick energy intake especially for mild cases of hypothermia

Proteins - 5 calories/gram - slowly released - heat given off over a longer period

Fats - 9 calories/gram - slowly released but are good because they release heat over a long period, however, it takes more energy to break fats down into glucose - also takes more water to break down fats leading to increased fluid loss

Food intake

Hot liquids - calories plus heat source

Sugars (kindling)

GORP (trail mix): has both carbohydrates and proteins/fats

Things to avoid

Alcohol: a vasodilator which will increases peripheral heat loss

Caffeine: a diuretic and causes water loss increasing dehydration

Tobacco/nicotine: a vasoconstrictor which increases risk of frostbite

3) Add Heat

Fire or other external heat source

Body to body contact. Get into a sleeping bag, put on dry clothing and make contact with a normothermic person in lightweight dry clothing.

Fresh snow dusting creates the most magical morning!

Frostbite

Frostbite occurs when extremely cold temperatures cause skin tissue to freeze. To preserve itself, the body stops circulating blood to these “disposable” parts. Ice crystals form, blood vessels clot, and tissue death ensues. Frostbite usually affects body parts exposed to the elements or parts prone to losing temperature faster, like the nose, fingers, ears, and cheeks. But frostbite can occur even when wearing boots and gloves.

How To Identify Frostbite

Frostnip is an early indicator of danger. The skin can be pale or red, feeling “prickly” or numb. You may feel a burning sensation as warm blood flows back into nipped skin. Fortunately, the damage isn’t permanent at this stage. (This most recently happened to me while breaking down my tent in freezing conditions at Charlotte Lake).

Superficial frostbite will turn frostnipped skin pale, cold, and numb. Fluids in the skin freeze. The tissue may feel warm but be cold to the touch. Rewarming will cause stinging, burning, swelling, and may lead to blisters.

Severe frostbite affects the deep, subcutaneous tissues below the skin. The skin will be numb and joints may no longer move. The skin might be hard and waxy-looking. Black, hard skin indicates tissue death. Blisters will occur after rewarming.

How To Avoid Frostbite

Cold skin is to be expected when you are out in the cold. But keep an eye out for early indications on the cheeks, nose, and digits – red skin, numbing, or a tingling feeling. These are all early indicators of freezing skin.

Traveling with others? Keep an eye on each other. Because numbness is often a key indicator, the victim may not even know they have frostbite until it’s too late.

Dress appropriately for the conditions, wearing layers and staying dry. Pay particular attention to your feet, hands, and ears.

If you are predisposed to cold digits, consider using heat packs for boots and gloves, especially for little ones who are more likely to get frostbite.

Treating frostbite

Get inside: Treat as you would for hypothermia. Hypothermia is a more dangerous threat and should be ruled out or addressed first. Remove wet clothing and get into warm, dry clothes.

Don’t walk on frostbitten feet

Rewarming should only be attempted if there is no chance of refreezing, which can cause further tissue damage.

Immerse the frozen areas in warm (NOT hot) water. Frostbite inhibits your ability to feel temperature, so victims should have someone help them prepare a warm bath between 100 and 108 degrees Fahrenheit. If a warm bath is not possible, rewarm the affected areas with body heat.

It is not advised to rewarm frozen feet if you are in the backcountry. Once frostbitten feet are rewarmed, it is impossible for the victim to walk out on their own.

Do not rub the frozen area or use heating pads or stoves to rewarm frostbitten flesh. The tissue is extremely vulnerable and can easily burn.

Heart Lake on our hike back out to Onion Valley (perfect weather on day 3).

Kearsage Pass on a clear day. These views look much different from the photo where I am standing in a storm, flipping the bird.

For a personalized account on winter hiking from a very well known and experienced hiker in the community check out Bill’s blog entitled “To the "Experienced Hikers" New to Winter This Year”. Although Bill and I have very contrasting views on hike leaders and hiking groups, we both share the same views in regards to skillset and mountain safety.

Heading down to Bullfrog Lake…the storm finally began to clear but temperatures were still below freezing.

Thanks for reading!

Stay warm, stay safe and hope to see you on the trails

Xx

Kristen